The Politics of the Police Budget

Fact Checking the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Local Policing

Municipal budget season has come and gone.

Belts were tightened, pencils were sharpened, and the public had their say.

It’s a time when the tough talk on the campaign trail gets tested and lofty promises tend to hit a brick wall.

City Council sacrificed a few proposed budget lines and the drama of ‘Plazagate’ predictably continued.

The unfortunate reality is that municipal projects are plagued by endless delay, increased costs, and no shortage of frustration.

Municipalities are perpetually under stress to practice fiscal restraint while maintaining consistent levels of service delivery.

Curiously, there’s one budget line that’s been immune to fiscal restraint lately.

Although (ex) Mayor Christian Provenzano mentioned a few frustrating policy areas in his exit interviews, a major one included the ballooning costs of policing.

The public only sees a tiny fraction of what happens behind closed doors, so it’s always refreshing when someone can be candid for a moment.

Provenzano provided some basic accounting for public consideration.

In 2015, the SSMPS spent approximately $25.5 million.

In 2021, the SSMPS spent approximately $32.4 million.

In a span of six years, the SSMPS budget expanded by almost $7 million, or more than a quarter (from its 2015 level).

This raises a simple but important question: is the community of Sault Ste. Marie getting good value for dollar for its investments in policing?

During the most recent municipal election campaign, City Councillor Luke Dufour apparently said the quiet part out loud.

In response to a constituent’s question about police presence downtown, Dufour mentioned that the ‘quadrant system’ used for patrol deployment could probably use some rejigging to make sure the areas responsible for the most calls for service have commensurate attention from police. Instead, the present system is mostly based on geography, which Dufour said prevents the implementation of a ‘dynamic model’ based on data collection and analysis.

In a nutshell, the ‘quadrant system’ splits up the city into four patrol areas that roughly see the same amount of deployment. It doesn’t mean that calls for service from one quadrant won’t attract the attention of officers assigned to others, but it nonetheless deploys resources across the city in a way that doesn’t necessarily align deployment with statistical need.

It’s no surprise to anyone that the downtown isn’t getting the attention that it deserves. That lack of attention explains a few things:

Why downtown residents have been complaining for years.

Why Dufour (among others) is keen to see a greater police presence downtown.

Why the SSMPS has pursued what it calls the ‘dynamic patrol initiative,’ and also why the it’s so keen to emphasize its presence downtown.

Why private security is required to keep watch on the downtown overnight.

Even though the problem is clear to anyone that’s paying attention, the response to Dufour pointing out the obvious was extraordinary.

The head of the rank-and-file police union, Joshua Teresinski, penned an op-ed to SooToday the day after Dufour’s comments were reported.

Teresinski alleged that Dufour had spread “false statements” and “misinformation.”

Further, he said the misunderstanding stemmed from a healthy distance between armchair critics (like Dufour) and boots on the ground (like Teresinski and his colleagues).

Dufour then offered a polite response admitting that he was “perplexed” by the allegations. In his response, he said:

The patrol deployment system is determined by geography and the union contract rather than by data driven neighbourhood needs or the priorities of the Chief/Administration. At no point did I suggest, allude to or state that emergency call responses were governed or constrained by the quadrant system.

To be fair, it’s easy to appreciate the thin skin of the union.

Local policing has seen a variety of additional pressures placed upon it, including greater calls for diversity and transparency, largely because of high-profile controversies across North America. There are also systemic social issues like addictions, homelessness, mental health, and organized crime, all of which overlap in drastically higher incidences of violent crime.

These pressures on policing are manifesting themselves in burnout, low morale, poor mental health, and more than enough resentment to go around. From a human resources perspective, it’s becoming more difficult to maintain a cohesive, healthy, and stable workforce.

Nonetheless, we need to have an honest and open conversation about local policing, especially because it accounts for a significant municipal expenditure and the city’s social woes are getting worse and not better.

The duelling op-eds weren’t the only skirmish though.

In an odd turn of events, Dufour was somehow dragged into the police budget presentation during the January 23 City Council meeting. According to one of the presentation slides, Dufour is included in a list of increased demands placed upon the SSMPS.

Although Dufour was a bullet point in Chief Stevenson’s presentation, the latter didn’t actually utter the former’s name. Instead, Stevenson referred to several individuals and groups that have asked for a greater police presence downtown.

The bigger takeaway is the degree to which human resources challenges are taking their toll. Chief Stevenson’s presentation noted that almost 10% of SSMPS officers are on leave and there are a few more (5.6%) that cannot be deployed in the field. The situation is “leading to unprecedented overtime above budget.”

Given this context, and the broader context of a tight municipal budget, there’s an expectation that efficiency and effectiveness will be the top priority.

So, did Dufour spread “misinformation” as Teresinski alleges?

To be clear, this question has nothing to do with whether one believes the average officer is doing a good job.

It’s only about whether the deployment of current police resources is done as efficiently and effectively as possible.

Not only could doing something differently improve public safety, but it could also mean less waste and more community value.

Further, there’s not necessarily friction between efficiency and the wellbeing of the rank-and-file. Savings in one area of the police budget could be strategically reinvested elsewhere to help relieve the pressures previously described.

Based on extensive research that the SSMPS commissioned itself, Teresinski’s claims appear to be suspect, at best.

In early 2017, a major accounting firm (KPMG) delivered a report to the SSMPS and Police Services Board, titled Strategic Plan for Transformational Change Review. Its recommendations are organized into eight different focus areas, one of which is ‘resource management.’

I received the report through a freedom of information request.

It wasn’t released in full, however.

The SSMPS redacted a few portions, including an entire page of the report focused on its ‘divisional map.’

The first objective of KPMG’s research is described like this:

Understand whether SSMPS is meeting the needs of citizens and clients as efficiently and effectively as possible, and identify ways to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of SSMPS.

In its analysis of patrol deployment in relation to the nature and frequency of calls for service, KPMG has quite a bit to say.

The major point is that there’s a disjuncture between calls for service and the structure of patrol deployment.

According to the report [with emphasis added]:

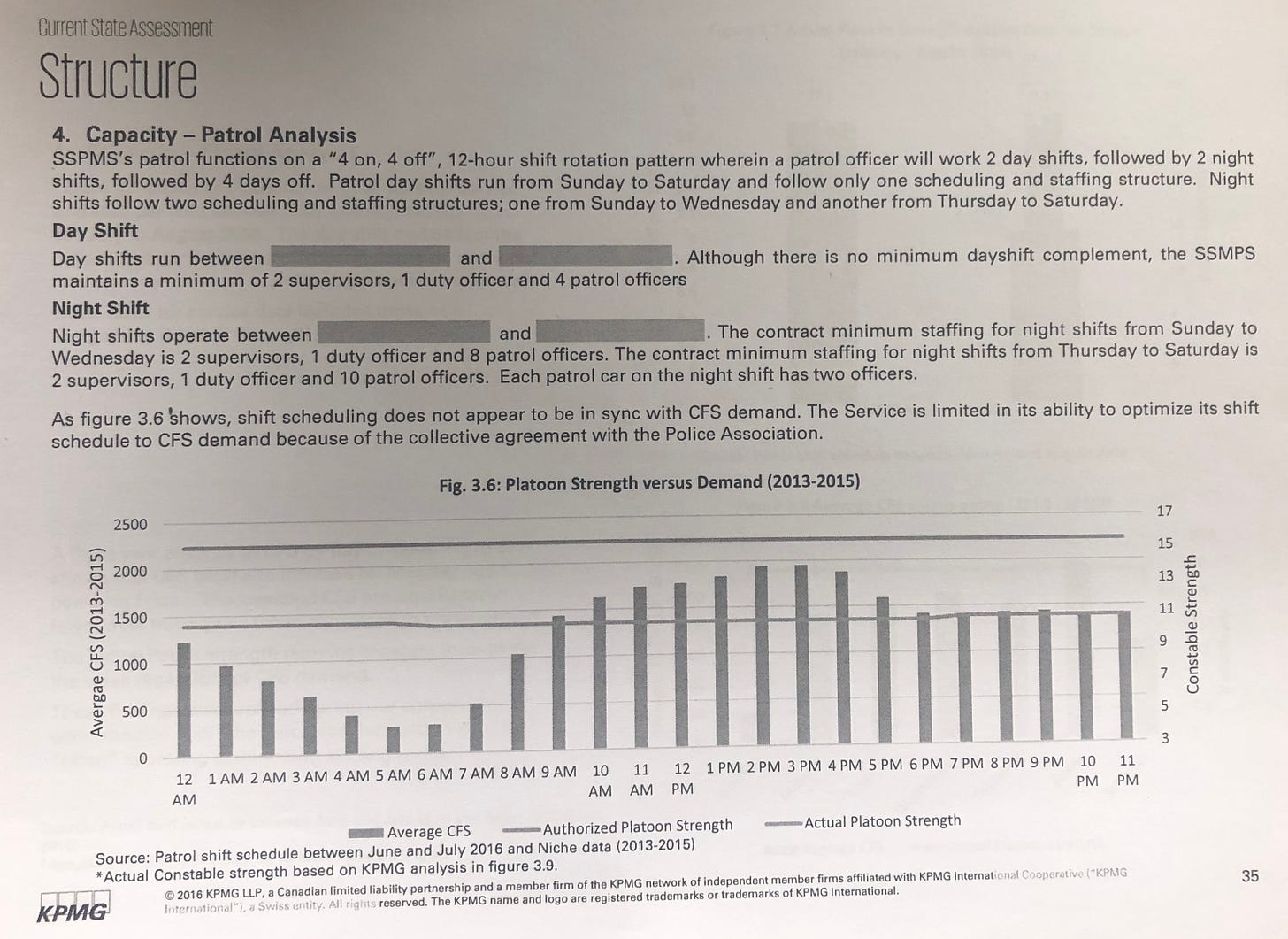

[S]hift scheduling does not appear to be in sync with [calls for service] demand. The Service is limited in its ability to optimize its shift schedule to CFS demand because of the collective agreement with the Police Association.

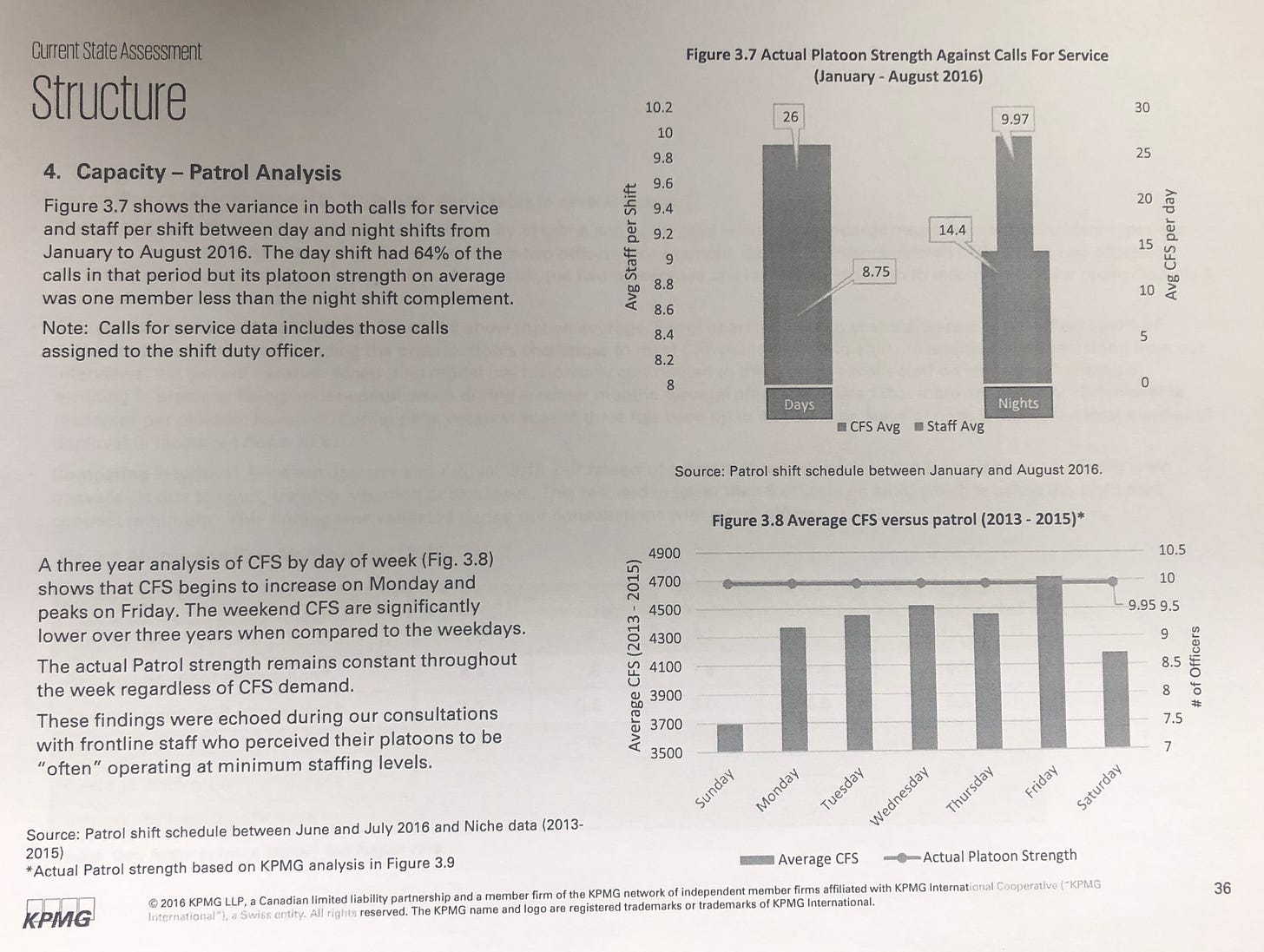

KPMG also highlighted the fact that patrol deployment is consistent across the weekly schedule despite a dip in calls for service during weekends. Here’s how they describe that:

The weekend CFS are significantly lower over three years when compared to the weekdays. The actual Patrol strength remains constant throughout the week regardless of CFS demand.

Similarly, there’s a dip in calls for service during the night shift, despite consistent deployment. Again, according to the report:

The static resourcing of the night shift does not reflect the significant drop in CFS demand.

In its recommendations, KPMG suggests reviewing the practice of having two officers per vehicle during the night shift. Despite that arrangement being contractually obligated, it might be inefficient and contrary to best practices.

That recommendation reads:

Review the use of two officer cars for the night shift. The SSMPS is contractually obligated to deploy two officers per car for nights. The trend in larger police services is towards single officer cars. Given the current state of technology and the size of Sault Ste. Marie there is an opportunity to increase the capacity of patrol – dependent on negotiations between the Board and SSMPA.

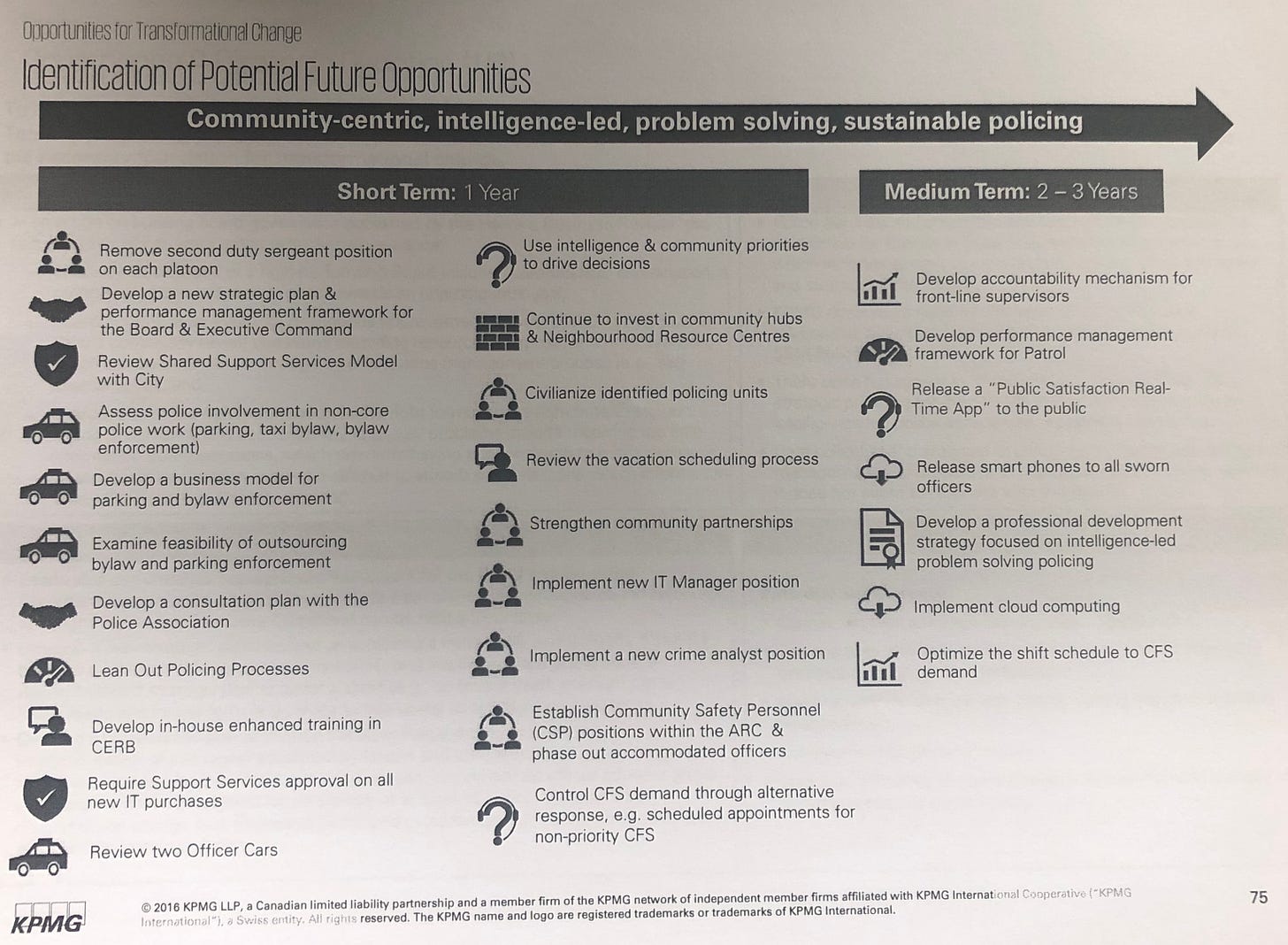

In sum, there’s room for efficiency and effectiveness improvements at the SSMPS.

The data that made up the report are slightly dated, but the collection and analysis of data itself should be happening consistently.

Far from ‘false statements’ and ‘misinformation,’ a data-driven approach to match finite police resources with community need is precisely the direction the SSMPS needs to go.

It doesn’t bode well that something so uncontroversial immediately provokes defensiveness and finger pointing.

If the community can’t have honest discussion about important issues, municipal policymaking inevitably suffers.

Given the enormous social challenges confronting local police and the community at large, the consequences of bad policy are likewise enormous.

If a simple question about the effectiveness and efficiency of policing is so difficult to ask, it’s only because it’s so important.