Steel Town (Still) Down (?)

How A Documentary Shook Sault Ste. Marie Five Years Ago and What's Changed Since Then

Five years ago, Steel Town Down shook Sault Ste. Marie to its core.

A collaborative documentary created by CTV and Vice, it shone a spotlight on the community’s struggle with addictions.

It found a national and even international audience, connecting the dots between complicated social problems and the grim realities of economic decline.

Unfortunately, the documentary would serve as a prelude for a deepening crisis in the wake of the global pandemic.

Title Sequence (Screenshot from Steel Town Down)

It’s fair to say that the local reaction to the documentary was mixed.

Hailed by some as a long overdue conversation with reality, it was panned by others who saw it as an overwhelmingly negative and skewed version of the community.

Steel Town Down connected viewers with health care and outreach workers, first responders, and politicians, all of whom painted a vivid picture of how poisonous drugs are leading to record numbers of preventable overdoses and deaths. Crucially, it allowed those who use drugs to speak in their own words, a privilege not often afforded to those at the margins of society.

While addictions remain a significant challenge for the community, the documentary provoked a simple question: are public health efforts proportionate to the gravity of the crisis?

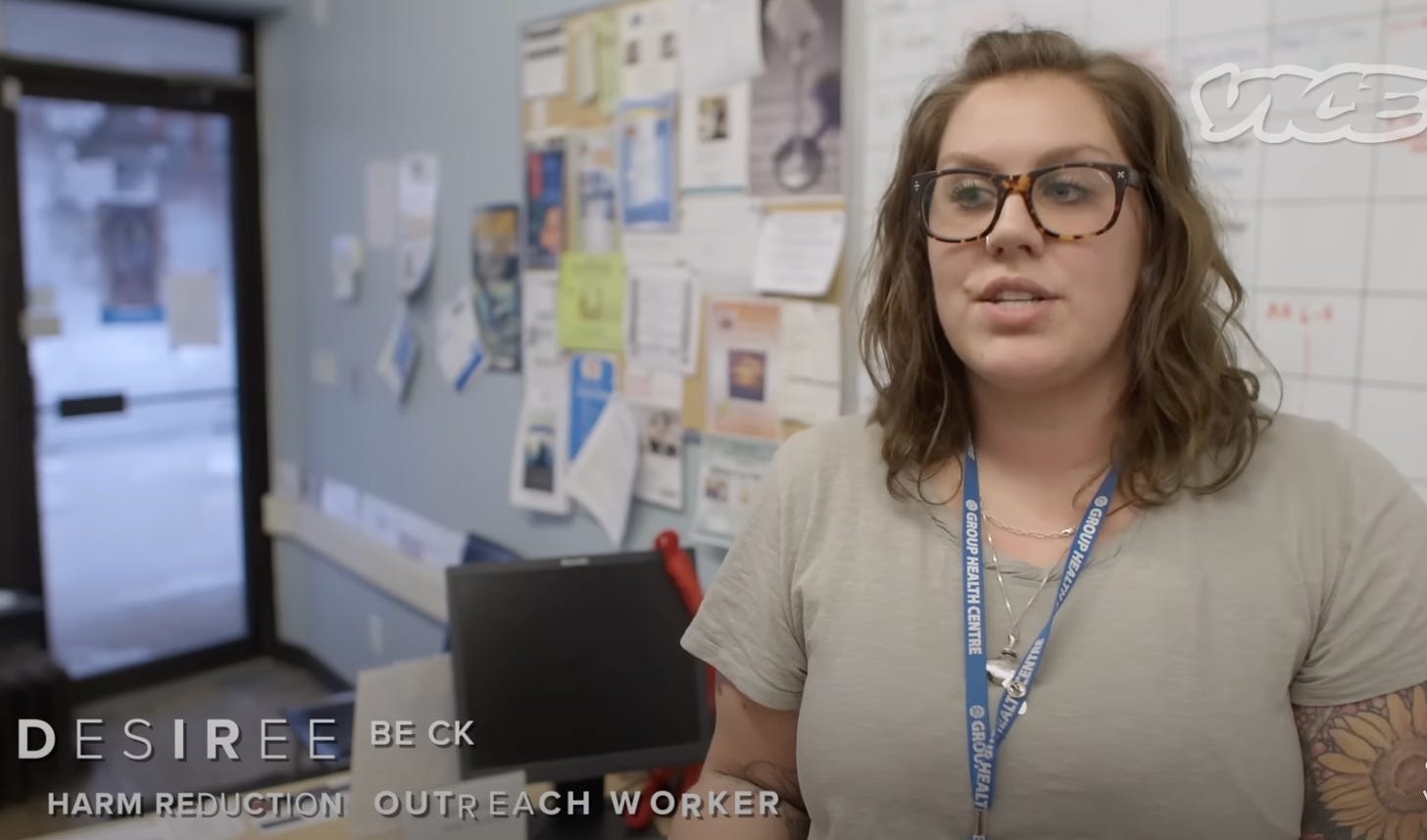

Desiree Beck had no idea she’d become one of the main protagonists of Steel Town Down.

To this day, she’s still uncomfortable with that spotlight, and prefers to focus on the issues at hand. As a long-time harm reduction advocate and outreach worker, she’s spent close to two decades with people struggling with addictions.

In a recent interview, she reflected on the legacy of Steel Town Down and how the conversation about addictions has changed in the past five years.

Introduction of Desiree Beck a the Community Resource Centre (screenshot from Steel Town Down)

Beck agrees that reactions to the documentary were varied, something apparent from her own experience.

Although she recounts receiving some “beautiful messages” from “all over the world,” she also endured a “backlash” and even some “hatred.”

One incident stands out.

She says she was once publicly “accosted” by a stranger who called her a “drug pusher” during an encounter in a grocery store with her children.

As a result of this experience and additional messages she received online, Beck developed some “social anxiety,” not fully appreciating the degree to which the documentary had gone viral, and the fractious local debates it would stir.

Nonetheless, she thinks these debates were important, even if they didn’t always feature a non-judgmental approach to those suffering from addiction.

At least part of the critical reaction can be attributed to an “ignorance is bliss” attitude, according to her. In general, the documentary showed her that “people are very uncomfortable with that conversation,” but given the gravity of the crisis, learning about addiction is an essential component of public health.

She describes various efforts before 2018, where outreach and social workers organized events and tried to raise community awareness. For Beck, it’s important to highlight this work, especially because the documentary took aim at the gap between services on offer and actual need.

In Beck’s words, “even if we’re doing the best we can, we’re still strapped because of funding constraints.”

Arguably, the most infamous moment of the documentary is a conversation between Beck and then Mayor Christian Provenzano.

When someone behind the scenes presented a statistic about average monthly overdoses in the city, Provenzano responded by saying that he was unfamiliar with it.

As a result, Provenzano bore much criticism for appearing ignorant of local statistics, something that would surface several months later on the 2018 municipal election campaign trail.

Then Mayor Christian Provenzano Speaking with Desiree Beck at City Hall (screenshot from Steel Town Down)

Beck says it’s important to realize the scene with Provenzano came on the heels of a long conversation without cameras rolling. She explains the “awkward” nature of repeating some of that conversation and worries that the scene was “skewed,” potentially creating the impression that her and Provenzano had an adversarial relationship.

Quite the contrary, Beck says that Provenzano “was always supportive of anything we had we had going on when… [she] was chairing the [City’s] drug strategy.”

Provenzano Discussing Local Overdose Statistics (screenshot from Steel Town Down)

When she founded Willow Addiction Support Services, a local organization that’s been advocating for a supervised consumption site, she also says Provenzano “was the first person to approach [her] and say that he would happily write a letter of support.”

Many of her social worker colleagues in Southern Ontario reached out and were envious of her opportunity to connect with a mayor, saying “we would never get that.”

Although there’s much to be desired for Beck, she does notice some tangible and positive changes that’ve happened since 2018.

First and foremost, “there seems to be more interest in people having the conversation,” and there are programs and services that encourage the involvement of drug users themselves. The latter is important, “so that we are not making choices for other people.”

She observes “Naloxone everywhere,” a relatively cheap and accessible medication that can immediately reverse the effects of opioid overdoses.

In particular, the proposal for a supervised consumption site is “a huge step in the right direction.” That proposal will require both provincial and federal approval, including an exemption from drug prohibitions and enough funding.

The process is daunting, says Beck, laden with “constant roadblocks” and “little idiosyncrasies” that can easily lead one to “feel defeated.” Progress is being made with the support of municipal leadership – reflected by Mayor Matthew Shoemaker’s major campaign pledge – but a recent setback came in the form of a proposed site being sold for other purposes.

There are broader challenges, too.

The pandemic unleashed much higher rates of local overdoses, a trend Beck calls “an alarming cue that while the world shuts down, the needs of people who are using drugs… were overwhelmingly impacted.”

She thinks the pandemic created a “ripple effect,” in which services and supports either ceased or were scaled back, and related social issues like homelessness and mental health likewise reached acute levels.

Interestingly, Beck says she’s never watched Steel Town Down in its entirety.

Due to its personal nature, including highlighting her connection with a friend who struggled with addiction and unfortunately passed away recently, the documentary brings her some unease.

In hindsight, she wants local journalists to connect with a wider array of those who provide frontline services, many of whom have knowledge and experience that should be a part of evidence-based decision-making.

When asked about what motivates her harm reduction and outreach work, Beck mentions a “moral hierarchy of substance use,” whereby some substances like alcohol are widely available, regulated, and socially accepted.

Conversely, other substances like opioids are unfairly stigmatized and subject to a double standard, one that results from an incomplete understanding of addiction.

“I will never accept the idea that just because people use drugs, they deserve less,” she says.

Stay tuned for a podcast episode featuring an in-depth interview with Beck.