Amid an Epidemic of Substance Abuse, Where Does Problem Gambling Stand?

New Statistics Provide a Glimpse of the Problem at Sault Casino

Over the last five years, the conversation about addiction and mental health challenges in Sault Ste. Marie has changed dramatically.

Most residents have seen with their own eyes the ravages of addiction, including a swelling homeless population and a surge in petty crime.

But not all forms of addiction involve the consumption of substances.

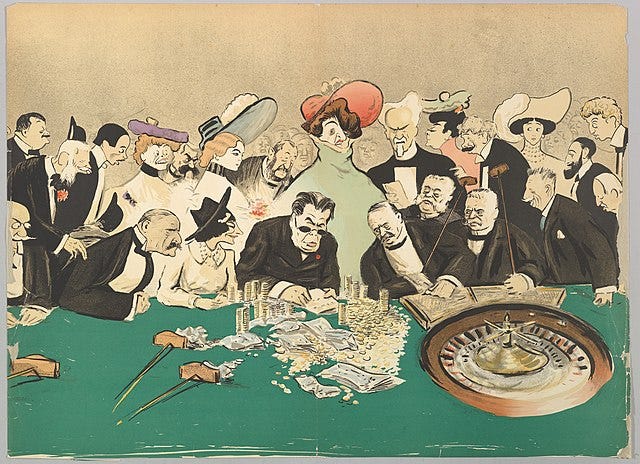

While gambling is a relatively uncontroversial leisure activity, some engage in it compulsively and destructively. For these people, gambling resembles the traditional qualities of addiction, including negative effects that can extend to family and friends.

Like alcohol, opportunities for gambling are ubiquitous. Much of it is regulated by the provincial government – ranging from scratch tickets to slots and gaming tables – and these activities provide a reliable source of public revenue.

Unlike alcohol, however, the potentially negative consequences of gambling are much less visible. Someone who gambles compulsively may not exhibit physical symptoms of addiction and their negative experiences – like a spiral of debt or reduced quality of life – may be highly individualized.

According to Victoria Orlando, an Addictions Counsellor at Sault Area Hospital, “gambling becomes a problem when it is done excessively and negatively affects a person’s daily activities, school or work performance, mental health, physical health, interpersonal relationships, and finances.”

Orlando says the activity “may occur over a continuum,” including leisurely gambling that’s done socially at one end and “pathological” gambling at the other end. Importantly, problem gambling can affect anyone, and it’s not confined to a specific segment of the population.

Widely accepted psychological diagnostic tools see problem gambling as a “substance-related and addictive disorder,” says Orlando. Therefore, gambling can exhibit some of the same pleasure or reward systems that characterize the consumption of addictive substances like alcohol or drugs.

She explains that problem gambling poses additional challenges for health care providers and social workers, because “its effects may not be immediately visible” and they tend to be “emotional, financial, and behavioural.” For these reasons, identification, intervention, and support efforts can often come after an individual has developed a dependency.

In a local context, most would associate the activity of gambling with the Gateway Casino on Bay Street. Originally established by the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Commission (OLG) in 1999, Ontario has since privatized the site among others across the province. OLG offers a variety of resources and connections to support those affected by problem gambling, mandated by the Alcohol and Gaming Commission of Ontario.

OLG bills itself as “a world leader in responsible gambling,” boasting 25 years of investments informed by “research and best practices to promote positive play based on informed choice.”

Its major offering is a provincial ‘self-exclusion’ program, which allows patrons to register in a system that can detect their physical presence at OLG-affiliated casinos. The My PlayBreak program is described by OLG as “a voluntary tool that makes it easier to take a break from gambling.”

Individuals can request self-exclusion for different lengths of time, ranging from three months to five years for in-person locations and one day to five years for virtual locations. If detected, those who are self-excluded can be escorted off casino properties for trespassing.

The program began in the mid-1990s and has since become standard across the province. OLG began employing facial recognition technology to assist the program in 2011.

OLG describes the latter as “a very effective tool for voluntary self-exclusion and our broader responsible gambling program.” It also says it’s recently implemented “enhancements” to the program in response to “an extensive review.”

The newest iteration of the self-exclusion program now “offers customers more flexibility and choice and removes barriers to register in the program.” Those who register can choose defined time lengths, opt for ‘check-in’ phone calls for potential referrals to additional support, and experience a smoother renewal process.

Although it’s been helpful for some and OLG “make[s] registration as easy and as accessible as possible,” the program has faced critical scrutiny before.

In 2017, CBC’s The Fifth Estate took an intimate look at OLG’s self-exclusion policy and practices.

It showed that despite the deployment of facial recognition technology, some individuals were able to routinely access casinos after enrolling in the program.

Experts that study gambling troubled the effectiveness of the program and further questioned why the responsibility for a systemic problem was being placed on individuals.

In 2010, a group of problem gamblers had their lawsuit dismissed, one that alleged Ontario casinos were failing to keep them away from their premises despite multiple requests to do so.

OLG has since settled other lawsuits related to problem gambling, some from claimants arguing that they suffered serious financial losses after enrolling in the self-exclusion program.

The problem of problem gambling is even more complicated when one considers the fact that OLG is one of Sault Ste. Marie’s largest employers, hosting its corporate headquarters since the early 1990s.

Since the establishment of the casino, the City of Sault Ste. Marie has derived almost $34 million in revenue from its operations, and the province of Ontario has seen billions in annual revenue derived from OLG-affiliated casinos.

By comparison, OLG says it spends more than $17 million per year on its responsible gaming program.

The casino is Sault Ste. Marie has featured facial recognition technology and a self-exclusion program for over a decade, as a part of OLG’s “comprehensive responsible gambling portfolio.”

Employees at the casino are trained to recognize symptoms of problem gambling, interact with those exhibiting such behaviour, and report such occurrences. This employee training, which includes collaboration with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, is “crucial in the efficacy of the programing and its continuous improvement,” says OLG.

New statistics obtained from OLG provide a partial snapshot of problem gambling at the Gateway Casino.

A freedom of information request sought the number of individuals that self-excluded at the Gateway Casino in Sault Ste. Marie between January 1, 2010, and May 1, 2023, and how many times self-excluded individuals were detected on site.

In total, there were 634 requests for self-exclusion at the Gateway Casino during that time period.

86 individuals made more than one request for self-exclusion, and they’re responsible for approximately 39 percent of all requests.

One individual made eight requests, two individuals made seven requests, four individuals made six requests, and four individuals made five requests.

During the same time period, the Gateway Casino detected self-excluded individuals on their premises a total of 429 times.

66 individuals were detected more than once, and they’re responsible for approximately 40 percent of all detections.

Two individuals were detected eight times and two individuals were detected five times.

The statistics don’t include detections of self-excluded Sault residents at other Ontario casino locations.

In general, statistics related to problem gambling at casinos can only reveal so much.

At the local level, determining the prevalence of problem gambling is “challenging,” says Orlando, and it may be the case that only a fraction of the activity happens in casinos.

The digital age has drastically expanded gambling opportunities and dispersed gambling practices into new spaces, like fantasy sports leagues.

Nonetheless, Orlando thinks local service providers “are well-versed in screening for gambling problems and asking the appropriate questions.”

Orlando also says support for problem gamblers is “relatively new” in the field of addiction support services. Historically, a lack of awareness of public health support and enduring stigma associated with addictions has complicated proper assessment and treatment options.

More nuanced conversations about addiction may be changing that.

Health care providers and social workers are progressively incorporating problem gambling into their assessment and screening practices, a vital step for data gathering and evidence-based practice.

For those struggling with problem gambling locally, the Addiction Treatment Clinic at Sault Area Hospital can offer resources and support to individuals and their family members, including treatment options within the community and financial counselling.

Other organizations that offer public education, resources, and support include the Ontario Problem Gambling helpline (1-888-230-3505), Gambler’s Anonymous (gam-anon.org), Connex Ontario (connexontario.ca/en-ca), the Responsible Gambling Council (responsiblegambling.org), and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (camh.ca).